The original Norwegian version of this post contains material that relates directly to the resolution on Integration Policy which was up for discussion on the session of the Socialist Left party National Board of Representatives 5th-6th September 2014. The English version has been edited to frame the analysis in a broader, societal frame.

A confession

I’m a racist. I think racist thoughts all the time. Perhaps not as often as I think about sex, but often enough that I’m frequently ashamed of myself. A surprising number of people will argue that this sounds like a paradox, given that I’ve got both a sister and a daughter who don’t look “ethnically Norwgian”. Seeing that I’ve not only got friends, but family ties with non-white children, it ought to be impossible for me to judge people by the colour of their skin, right? Nonetheless, I felt a sense of fear and unease as a guy who looked like he might be Romani passed me on his bike this morning. I immediately corrected myself, mentally. I don’t act racist — I try to be nice. But why did I feel like that? No Romani has ever hurt me or been a nuisance to me in my everyday life in any other way than silently sitting by the roads I walk with their beggar cups (which I regard as a human right). The obvious answer is that my thoughts were a distillate of the stories that I’ve been exposed to about Romani, many of which are not particularly nice — but neither are they my responsibility.

Polls have shown that in Norway, those who hold the most negative views about immigrants are those who’ve interacted the least with them (Norwegian .pdf pp143f). This illustrates the same point: The stories about immigrants are far worse than reality, and those who only have the stories to relate to therefore form opinions that are more negative than those who have real-life experience. Discourse is a term that describes a collection of stories in a given field. When it comes to how we as humans relate to people around us, discourses about Otherness play a significant role. We frequently define ourselves in opposition to someone on the outside of our community (in an abstract sense). We do this on a micro level, in the form of gossip, on a macro level, in the form of e.g. political antipathies, and sometimes it’s even done between countries and people — as in the Russian Slavophile discourse, which defines Russians and Russia in opposition to Europe. Some such discourses are entwined with shame, mostly because we know they’re unethical. I’ll return to this matter later on. For now, it will suffice to write that racism and xenophobia can be seen as outgrowths of discourses about the Other. This means that we should carefully consider which stories we hand on, and how we frame different subjects.

A third way?

Here, I’ll present an example of a framing that I consider to be unfortunate. Let’s begin by considering the construction of the term “integration policy”. The last part is “policy”, which in this specific context describes how the general society has decided to act on a matter. The first part is “integration”, which describes the process through which people — in a collective or singular sense — who are not yet full members of society can acquire full membership. Integration policy, thus, is the action society takes when it approaches an arriving minority. It’s a common fact that whoever defines a problem will incorporate their impression of reality into their definition. As far as integration policy is not informed by a perspective where the majority is forced to consider itself critically, society will always define the problems of integration in a manner that puts the responsibility in the hands of the arriving minority. The discourse on integration is necessarily a discussion about the Other.

This is reflected even in the policies of one of Norway’s most liberal parties, my own Socialist Left party. A resolution on integration policy passed in 2010 contains passages that are typical of the present Norwegian discourse on immigration.

Two opposing views have dominated discussions on integration. On one side, there are those who believe that minorities ought to become as similar to the majority as possible, and therefore have to give up their identity. On the other side, there is the view that different cultures in a society should cherish their differences and have separate values and ways of life, even when these are opposed to fundamental common values. The Socialist Left party works towards a third way in integration policy.

The third way is built on an insistence that there exists a set of fundamental common values and duties, but that a large space remains in which differences in ways of life, culture and religion may be realised. The Socialist Left party considers diversity to be a value in its own right. Democracy, gender equality and social equity are non-negotiable, fundamental values in the society we strive to build. We will struggle against all attempts to compromise these values, also when they are motivated by religion or culture.

Another passage which, despite an ambivalence, makes the point that Norwegian values stand in opposition to those of the Other, reads as follows:

A well-functioning multicultural society is preconditioned on a set of common rights and duties. The Socialist Left party strives to base the Norwegian society on democracy, gender equality and social equity. These are universal rights which have a strong standing in Norway as a result of political and social struggle over many decades, and not something that can we can take for granted as “Norwegian values”.

The construction of otherness

Let us now recall the construction of the term “integration policy”, and hold it up against this professed “third way”, and we see that when society’s approach to an arriving minority is considered, even the Socialist Left considers the arrival as a threat to society’s fundamental values. This is not a third way. Rather, as has been pointed out by several scholars in the fields of culture, racism and security policy (all are pdf links to research papers), it is a fundamental part of one of the most problematic discourses on Otherness that Europe presently has to deal with: That which tells stories of an alleged Islamic threat and has substituted religion and culture for race to perform an act of intellectual necromancy and raise the spectre of racism once again.

Thus, even one of the Norwegian society’s most progressive voices is unable to avoid placing the blame for societal malfunction on the arriving minorities. In doing this, better explanatory variables are overshadowed, and more precise definitions of societal problems deferred: The negative discourse of integration is continued and the stigma placed on the Other increases. If there is a third way, surely it must aim to move beyond this negative discourse.

Breaking the taboo

Above, the entanglement of some discourses about the Other with shame was discussed. The discourse on integration, it seems, is growing — even though it has such entanglements. The “integration perspective” is introduced on a growing number of fields, and frequently in areas where it would, until recently, seem absurd to find such a perspective. One such case is that of head garments as part of public uniforms. In Norway, a sikh served in His Majesty’s Royal Guards with a turban in the eighties (see facsimile). It was considered a curiosity. When the use of hijabs in the Defence was discussed quite recently (or even more acutely, hijabs on police officers or judges), it was framed as a threat against fundamental societal values. Now, however, there’s many more than that single Sikh, you might argue, it’s the sheer numbers that has made this an issue. However, that’s simply not true — the issue is largely a hypothetical one.

I find an interesting parallel to this in Michel Foucault’s “The History of Sexuality”, where he shows how the concept of sexuality as a part if human nature and identity, not to mention the term itself, is a relatively recent invention. He writes about how the sexual is taboo, entwined with shame, and regarded as something primal, over which it is attempted to achieve control by explicitly thematizing it in public. “We must dare to have this discussion,” is a trope that is widely recognised as a cliché (at least in a Scandinavian context). It has been masterly deconstructed by Swedish MP for The Left Party (Vänsterpartiet), Ali Esbati. But the fact that we have acquired knowledge about the function of this trope has not stopped us from being its thralls.

The collective self-denial of individual liberty

As Esbati deconstructs the trope of alleged moral courage, Foucault shows that the modern public discourse on sexuality is really limiting, despite, or rather because of, its incessant explicitness. As with racism, the taboos of sexuality are so stubborn that it is still possible to frame plays on one of literary history’s most dominant tropes that of the whore versus the madonna as an emancipatory project. A treatment of this which is both acadmically stringent and stands in historical continuity with current Norwegian discourses can be found in Gro Hagemann’s work (cited from Svein Atle Skålevåg: «Kjønnsforbrytelser, sedelighet, seksualitet og strafferett 1880-1930» (“Sex crimes, Vice, Sexuality and the Penal Code 1880-1193”, in Norwegian):

[In Hagemann’s view], the defining schisma of the cultural debates of the 1880’s was a divide between an individualist cultural radicalism on one side and a societally oriented cultural conservatism on the other side (exemplified by Monrad), which was concerned with the collective morals. In this conflict, the question of women’s emancipation became “the debate’s most flammable issue”.

The opposition between individualism and collectivism constituted a “moral dilemma”, which, for its part, was immanent in the fabric of the feminist project, in Hagemann’s opinion. “The debate about vice accentuated an ambivalence that had been latent in the women’s movement from the very beginning. And over time, a shift in the relationship between the two positions took place. While the cultural radicals in the 1870’s and 80’s broadly speaking supported an equity-oriented feminism, women’s organisations in the 1890’s to a greater extent reflected a values-oriented conservative position focused on gender differences.

At this point, it seems appropriate to highlight which side in these debates which used traditional values to frame the Other as a threat: Those who would conserve the societal status quo, the sexuality and societal order which they had come to regard as normal.

The attack on normality

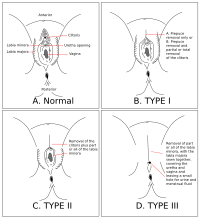

Returning to the term “integration” in the Norwegian context, it is clear that the opposition our – Other is an inherently conservative framing of the issue. Frequently this is embellished with lists of phenomena belonging to the Other: Typical themes of “integration” are forced marriage, women and children’s exposure to domestic violence, social control, extremism, genital mutilation and demands of separate boy and girl classes. Here, I would like to restate some of the main points of Ali Esbati’s piece, which I referred to above: The result of these debates on integration isn’t that we arrive at new solutions. The result of framing the problems as issues of “integration” is also not the formulation of a powerful policy to bridge differences in the general society. On the contrary, the debate on integration serves as a quasi-legitimate coat rack for emotions that can’t be legitimately expressed in other contexts, and lists of the above type leads the thought toward the general typologies for demonisation of the Other (Norwegian, .pdf). To many it is even an opportunity to thematize taboos — as long as it is done within certain rules.

Integration policy thus becomes an excuse to collect all problematic issues where immigrants are overrepresented under one umbrella. People of Norwegian ethnicity are wildly overrepresented among persons committing internation tax evasion crimes (in a Norwegian context) and among persons who serially import women from Eastern Europe and Asia in order to marry and beat them. We don’t make Norwegian-political resolutions to discuss these issues. To many, even the notion of doing so seems absurd. But it doesn’t seem absurd to collect all forms of problems where immigrants are over-represented in integration policy, and thus use this field to underscore the attack that immigration, allegedly, mounts on “normality”, “the Norwegian”, or “tradition”.

A positive project

Having mounted an attack on the notion that a third way has successfully been paved out — what do I propose in stead? Is there a positive project to be found in this criticism? In my opinion, the first step is to make the matter of integration as small as at all possible. We need to include the Other in the We that formulates policies regarding Us. Integration policy needs to become a matter of the mere first steps: The help, support and incentives that are the new arrivals’ very first meeting with our society. Next, we need to get used to the phrase “this isn’t about integration, it’s about the social or material circumstances.” Integration policy can only be ethical if it remains entirely positive in its perception of the Other.

Many of the subjects that are currently treated as matters of integration will continue to be important in political discourse. However, in stead of integration policy, consisting of the perspectives of the welfare, regulatory and judicial institutions on immigration (or the Other), we need to address specific issues in specific contexts: People with a different country background than Norwegian are probably over-represented in the target group of the Child Protection Services (CPS), at least in Oslo. That’s a matter of CPS policy and not immigration policy, because it concerns the CPS and not a public institution of immigration.

What about my racism — can I get rid of it? Hopefully, I can, but there’s an obvious need for a lot of help from everyone else. To paraphrase a frequently misunderstood quote by Thomas Hylland Eriksen (Norwegian newspaper article): We need to deconstruct integration policy until it’s impossible to speak of integration as a singular phenomenon or immigrants as stereotypes ever again.